By Cathy Clamp

By Cathy Clamp

Before Twitter and Facebook, the fastest way get a story on the news was on a BMW R50/2 motorcycle. In 1972, every network or television station used couriers to get important stories delivered. It was the fastest way to get around Washington, as well as the quickest way to get killed.

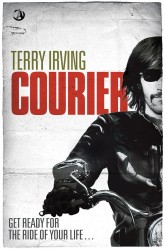

From four-time Emmy award-winning writer and producer Terry Irving comes a thriller as hard hitting as Watergate and as deadly as the Vietnam War. Not only is Irving the recipient of three Peabody Awards and three DuPont Awards, the former motorcycle news courier has been a producer, editor or writer with ABC, CNN, Fox and MSNBC. You won’t get more “inside” Washington politics than this book. Why else would legendary reporter Sam Donaldson give his highest praise, “Kudos to one of television’s best producers for writing the thriller of the year,” while NBC Nightline’s Ted Koppel said, “If the phrase ‘a crackling good yarn’ evokes an era before Twitter, Facebook, cell phones, videotape, DVDs or cable television, welcome to Terry Irving’s fast-paced thriller.”

The hero of COURIER is Rick Putnam, a Vietnam veteran and motorcycle courier for one of the capital’s leading television stations. He’s trying to get his life back together after his nightmarish ordeal in the war. But when Rick picks up film from a news crew interviewing a government worker with a hot story, his life begins to unravel as everyone involved in the story dies within hours of the interview and Rick realizes he is the next target.

THE BIG THRILL sat down with the author to ask him more about this intriguing thriller:

Setting the book in the Watergate era is an interesting choice, since so much of the news was focused on that issue. What made you choose this time period as a setting, or is it based on a real-life event?

I moved to Washington, D.C. after I graduated from college in 1973 and—after bartending, loading steel rods, and helping drive a school bus to Alaska—got a job as a motorcycle courier for ABC News. So, yeah, it’s based on a real-life event. Not the events as depicted in COURIER but the wonderful bright memories of spending eleven hours a day on a BMW motorcycle crisscrossing the nation’s capital. There are just times in everyone’s life that stamp themselves so vividly in memory that you never lose them. Driving in and parking my bike inside the White House, sitting on the floor outside Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox’s office during the Saturday Night Massacre, standing high on marble stairs as Vice President Spiro Agnew was brought into court to plead nolo contendere to accepting bribes. Big events like that and small ones like sliding on Metro subway planks, being so cold that my hands were cramped around the handlebars, braking desperately as some fool ran a light, or racing another courier way out in Maryland and realizing I was going way too fast for the corner.

It’s been over forty years and those memories are actually clearer than anything else I’ve done for at least the past twenty. Not that my adult years have been boring but they didn’t have the knife-sharp clarity of the courier days. What I used from that time was the feeling of Washington as a smaller, more intimate city; the gut-wrenching excitement of a powerful motorcycle, and the wonderful people. I was actually surprised when I began to write COURIER in 2010 and realized that it was as alien a time as Victorian London to anyone born after 1990—a place where there were only token blacks and women, no gays or other minorities, everyone smoked everywhere, many of the top people in news didn’t have college degrees, and they put on television with a lot less expensive equipment and a lot more ingenuity. A world, frankly, that was far closer to 1940 than 2010 and where most of the white men who ran it wanted it to stay that way.

Watergate itself was the overwhelming story of the time—it went on for years, with reporters and camera crews sitting in lawn chairs outside Judge Sirica’s court for nearly a decade, and from the time I was still in college (and used to turn on the hearings in the bar I worked in to provoke arguments and increase alcohol consumption) to long after I’d finally gotten a full-time entry-level job at ABC and started a real career—it was the primary fact of life. It was not, however, a story that I covered. I wasn’t digging into the backgrounds of Haldeman and Ehrlichman (although I almost drove the bike across a Metro dig on an I-beam to follow one of them). it was just the world in which I lived.

As a journalist, you’re accustomed to digging facts out of hints, glances, and body language. Was it difficult to make the character not share those traits so that Rick has to work harder to find out the same information that reporters might have grabbed onto quicker?

I’ve always felt the urge to say, “Excuse me, I’m not a journalist. I work in television. You probably want to talk to one of the newspaper guys over there.” Part of that is true.

For years, my jobs involved getting scripts to the right places at the right time—usually at a dead run, dividing out graphic gels so that a picture of Patty Hearst didn’t appear while the anchor was talking about the rise in genital herpes, or standing in a tape room two stories underground in New York and creating a story by live-calling changes between three separate tape recordings and an incoming live satellite feed. As a producer, my job on the road was to make sure we could pay for whatever we needed to do (I hand-carried $77,000 in cash into Beirut once), keep everyone from correspondents to soundmen sober enough to do their jobs, and always have a second and third and fourth way to get a story out if there was no time, no satellites, or no taxis. (In the “no-taxi” case, you walk into the road, stand in front of cars until one stops and offer $50 for a ride to the TV station. It works if you talk fast enough.)

As time passed, I suppose I did become a journalist. I was always a researcher and eventually the links between Story A and Story B began to penetrate my thick skull. I was able to handle the logistical challenges with a lot less attention so there was more time to follow the story and, after I covered the campaigns in 1980 and moved to Nightline in 1981, I became a full partner with the correspondent in the reporting and editing of stories. Later, at several programs, I was the guy in the field; I reported the story, directed the coverage, reviewed the video, and wrote a script for someone else to read. For most of the past twenty years, I’ve written for anchors and correspondents or done scripts for documentaries. Or financial planners. Or the Navy’s Dental Graduate School.

So, yes, I definitely became a journalist but I sure wasn’t one back in 1973 when I was twenty-one years old with all this nonsense from college in my head that later turned out to be incorrect and a lot more concerned with cutting a fast corner or having my first twenty-dollar dinner than worrying about what particular law Richard Nixon was breaking.

Along with simple invention, the character of courier Rick Putnam is based on a whole lot of people, but I’m not one of them. He’s smarter, tougher, and a lot better looking. He rides a motorcycle like he was born on one and he has nightmares and demons in his head that—as someone who did not serve in Vietnam—I had to extrapolate from the lives of people I knew and the writings of those who were there. One of the few things Rick and I share is the fact that, in 1972, we were living our lives—not covering the lives of others.

A lot of readers grew up in the Watergate era, so this will be a little of a coming home to many. But for readers who grew up in the computer generation, what’s going to be most striking about the era or setting?

I think two things will strike them. One is the complete and absolute antipathy to women and minorities in the workplace. My high-school class had at least a dozen people who were in the first coed classes at colleges like Yale, Harvard, and Princeton. When my girlfriend wanted to be a lawyer, she was told that only five percent of law school students were women and that she would have to go into government because no law firm would ever allow a woman to take lead on a major case. I remember there being one black correspondent and one female correspondent at ABC when I arrived and about the same number of managers and producers. The people that I grew up with simply didn’t share this way of looking at the world—not all of them, but enough so that I rose up through the news business in a crowd that included women and minorities. If not exactly the same ratio as the population, it was a lot closer than the people who came in two or three years ahead of me.

I watched the first woman engineer set studio lights (all completely jumbled by the old white engineers), black producers and correspondents fight their way onto major stories, gay men and women became visible—willingly or unwillingly. Now, women probably run more newsrooms than men do and they should; they’re tougher, smarter, and they work harder. Black men and white women fall in love and get married—both on television and in real life…

I could go on but I just sound old. The primary point I’d want to make is that, when these terrifying, world-shattering changes finally did happen—life just went on. This country certainly isn’t perfect about the way it handles diversity but I’ve come to realize that it’s much, much better at it than anywhere else in the world.

The second interesting fact is that I was totally wrong about Watergate. Along with the vast majority of the nation, I thought that Nixon had done something but that a great deal of the scandal was simply political. Only total cranks and unreconstructed leftists believed that the Nixon White House was really very different from all the administrations that came before it.

What I’ve found in my research is that it really was different. It was a vast and dedicated criminal enterprise that not only did everything the most radical accused it of doing, but far, far more. Most people in the U.S. became so tired of Watergate that they tuned it out. The books that amazed me are the researchers who continued to cover the story through decades of court trials, corporate confessions, tell-all books, and deathbed confessions. Renata Adler at the time, and Fred Emery and the BBC in recent years, have done an amazing job of presenting this but it’s had a small effect on overall public perception.

The Attorneys General appointed by Richard Nixon were committing felonies; the CIA and FBI were acting outside the law—even if there had been laws to control them—millions of dollars were donated anonymously and, I believe, are still unaccounted for today. In COURIER, I construct a fictional link between the Nixon White House and South Vietnam in 1972 but President Johnson’s recently released audiotapes show him telling Senator Dirksen that Nixon deliberately went to the South Vietnamese and spiked the peace process in 1968. President Johnson flatly describes it as “treason.”

Just consider. If there had been a peace agreement in 1968, how many more American soldiers would have come home alive? How many would never have faced the prospect of death, physical and psychic wounds, and destroyed lives?

Now, with all this said, I am not a Watergate historian and I make no attempt in COURIER to change history. I think that what I lay out as the basis of a thriller is completely possible. I do not claim that it’s true.

Did you make use of the memories of fellow journalists of the time to get that feeling of time and place? If so, who?

COURIER is the first novel I’ve written. I’ve never taken a creative writing course (nor a journalism course for that matter). I was out of work and a bit desperate in the summer of 2010. I’d been thinking about writing a novel for years and decided it was time to “put up or shut up.” I began COURIER in July and had it about eighty percent done by Labor Day. For a few weeks, paying work got in the way but that didn’t last long and I was free to return to writing and have it through the third draft by about November.

I don’t have an outline of a book when I begin, much less a chapter-by-chapter breakdown of character ‘beats” or whatever. Sometimes, I really don’t have a clue who is going to show up and turn into a major character until they…show up and become a major character. I do a massive amount of research while I’m writing—from Vietnam to How to Write a Damn Good Thriller to old maps of what was standing next to something else to 1972.

Originally, Rick was going to be based on Terry Irving. It only took about a day for that idea to fail miserably. Then, I began to build him from bits and pieces as varied as a picture of Nick Cage on a motorcycle to people I went to college with, to reporters I worked with. In the beginning, he wasn’t a veteran and then I wrote the first chapter. Once I knew that he’d been in Vietnam, I had to read a lot to understand where he’d served and what the war had done to his body and his mind.

There is an article from Life magazine that an amazing reporter, the late Jack Smith, wrote about the Battle of Ia Drang when he was nineteen and only weeks after he was almost killed in the battle (it’s online and really should be required reading). The movie, We Were Soldiers Once … And Young was based on the same battle. Another ABC reporter, the late Roger Peterson, was told that he’d never regain the use of his arm after being injured in Vietnam. I can still remember him squeezing a pink rubber ball and he was the strongest guy in the bureau as well as the nicest. I used all these bits and pieces and then added in a lot more that just seemed to fit. I try not to read any recent books on a topic—like Joe Galloway’s book on Ia Drang or George Pelecanos’s incredible depictions of Washington in the seventies—to avoid unconsciously ripping them off. However, the Internet is a wonderful thing. I had the front page of the Washington Post and the New York Times printed out for every day that goes by in COURIER—just to check the weather and sports.

It’s a process I’m fairly used to from programs like Nightline and NewsNight. You get assigned a story, pull about a foot-high stack of research, do your interviews and from that, you begin to build a picture of How to Build an Aircraft Carrier, or The Lies Told About Iran-Contra. This picture changes constantly as you learn new things and, often, changes completely if the facts are strong enough. In the end, you distill what you have and make an honest effort to squeeze this massive amount of information through the television set in a way that the viewer gets the most accurate, least biased picture possible of what you think is the truth. (Then you get ready to change it if new facts are presented.)

In COURIER, Rick changed completely.

He was far from alone. The man who is trying to kill him is driven by the horror of an event in Korea that I read about just before I wrote it into his backstory. Eve Buffalo Calf, the woman who breaks through the steel shell around Rick’s heart, was a two-dimensional plot device that just kept growing on me.

In the end, a hell of a lot of COURIER just happened. I’d come to a place in the story, stop for the night, and in the morning a whole new avenue would open up. The only thing I tried to do was to make everything I wrote something I could see happening in my head—if something just didn’t ring true, I deleted it. I was as surprised as I hope the reader will be when I found how so many parts of the book fit together—how the Seventh Cavalry’s bugles play in every character’s backstory, how the more I learned about Vietnam and the treatment of the returning veterans, the more it would explain Rick’s desperate self-isolation. Hell, my favorite characters, Rick’s computer genius roommates—who were based a bunch of guys I roomed with when I first came to DC—never played a big role in the story until they walked in and offered their services.

So, no. I didn’t talk to any of the people I worked with about the book. I did send it to as many of them as I could and asked for honest suggestions on where I’d gone wrong—fully expecting to be told off about some aspect of the story or another. I got a lot of comments but not the wholesale “what are you talking about, you idiot?” that I halfway expected.

Will you be touring as part of the release? Is there a schedule online anywhere for readers to find you?

I have no idea. Frankly, I have no clue how to sell a book in any way, shape, or form. I may end up on street corners with a sign “Will Sell My Book For Food.”

It’s going to be a wild ride.

Where can readers find you on the web? Website, Facebook, Twitter, etc.?

A better question is whether readers can ever escape me on the web. When Angry Robot purchased Courier, they decided that they weren’t going to publish it for almost eighteen months. In those months, I wrote the sequel to COURIER and the first book in a paranormal thriller series, put two rants and a partial memoir up on Kindle, edited a book about a Second American Civil War, and wrote the screenplay for a COURIER movie. In the time left, I decided to mount my own social media campaign.

Beginning with my website, there is a blog about other blogs called “Hey Sweetheart, Get Me Rewrite,” a blog about other writers called “Tired of Talking about Myself,” a blog about terrible job ads (“And They Say There Are No Great Jobs Out There,”) and a blog about surviving unemployment (“The Unemployed Guy’s Guide to Unemployment”). There is a COURIER Page on Facebook, an insane resume on LinkedIn, video clips of my past work on YouTube, and four boards on Pinterest. I’m gunning for 10,000 Followers on Twitter (thanks everyone) and 2,000 connections on LinkedIn. I answer questions on Quora, review books on Goodreads, hangout on Google+, and have beautiful homepages on places I don’t even understand like about.me.

Since I published the Unemployment book under a pseudonym, the pseudonym also has Facebook pages, a Twitter feed, and a Google+ page. Simply because I enjoy their ads, my pseudonym’s Facebook persona has one of the most complete lists of bail bondsmen online. Oh, and I run three very unsuccessful T-shirt stores on Zazzle.com and sell used books on Amazon. I know that there are other pages that I’ve abandoned—I may still have a Compuserve account and a Squidoo lens out there—but readers can reach me at terry@terryirving.com, terry.irving@att.net, terry.irving@gmail.com, terry.irving@hotmail.com, terry.irving@me.com, or simply say my name three times in front of a mirror.

Sadly, I’ve discovered that authors who plug themselves online are insanely boring so I generally don’t talk all that much about my books. I guarantee that will change once I have something to plug.

What’s next for Rick? Will there be further stories for him or is this a stand-alone?

As I write this, the publisher at Angry Robot is reading WARRIOR. the sequel to COURIER. (I finished it in September but he was just hired so I forgive him.) WARRIOR begins with Rick and Eve at the Wounded Knee protest in 1973, where they are plunged into a world of pseudo-religious cults and corporate greed (as well as two very fast motorcycles, a rocking RV, a homebuilt airplane, and a lot of explosives). These are the first two books in the Freelancer series with future stories planned in crime-ridden New York circa 1974, in Beirut with the Marines in the 1980s, and on the presidential campaign trail. Yes, I’m planning to continue to use my own life as the setting for these books but once again, my life has been nowhere as interesting as Rick Putnam’s.

I’ve written the first draft of an urban paranormal thriller, THE LAST AMERICAN WIZARD and I have the bones of a private eye series set in 1930s Manila in my head from all the research I did when I co-wrote a TV documentary called Rescue in the Philippines: Refuge from the Holocaust, which aired in 2012.

After that, who knows?

Tell us a little more about the Terry Irving that people might not know.

I met Ann MacFarlane in 1973—she plays a character in COURIER—and then we ran around with other people until we finally were married eight years ago. It is the sort of delightful second-chance story you read in a romance book but never really happens. If I put it in a novel, no one would believe it. I have two wonderful daughters and an increasingly cool grandson, a cuddly golden doodle, and an insane Balinese cat.

I sit in a home office so small I can probably reach any of the bookshelves without getting out of my chair. I’m sixty-two and unemployed (some say unemployable) and I’m desperately hoping that this book scam makes us enough money to keep watching Game of Thrones. On the other hand, I like working so I’d probably be sitting at the computer anyway, and writing novels is more interesting than a “make money at home” transcription-typing gig.

I have done a number of cool things and been to a number of cool places but you have to remember, I have always hung out with people who were a lot smarter than I was and had been to incredible places and created some of the best work in television. I have much the same attitude about writing. I’m not bad and I’m pretty fast but I’m not an artist like Charles Stross or Iain Banks or Barry Eisler or Walter Mosely or Lee Child or…or…or.

However, I do improve as I go along.

*

We’re willing to bet that readers will know just how cool you are after COURIER. It’s a thrilling ride!

*****

Terry Irving is an American four-time Emmy award-winning writer and producer. He has also won three Peabody Awards, three DuPont Awards and has been a producer, editor or writer with ABC, CNN, Fox and MSNBC. He is currently finishing the second novel in the Freelancer series, featuring Rick Putnam, of which Courier is the first. These stories will delight readers of mysteries and thrillers, as Terry weaves engrossing tales about the hard-hitting drama behind the headlines.

Terry Irving is an American four-time Emmy award-winning writer and producer. He has also won three Peabody Awards, three DuPont Awards and has been a producer, editor or writer with ABC, CNN, Fox and MSNBC. He is currently finishing the second novel in the Freelancer series, featuring Rick Putnam, of which Courier is the first. These stories will delight readers of mysteries and thrillers, as Terry weaves engrossing tales about the hard-hitting drama behind the headlines.

To learn more about Terry, please visit his website. Read the whole interview here!

You must log in to post a comment.